Machines Are Not Humans

Jaron Lanier famously wrote, "You are not a gadget." It turns out the inverse is also true: gadgets are not you.

By that, I mean machines are not humans. That seems pretty obvious, and you didn't need me to tell you that. And yet, we keep framing computers as people.

With the rise of generative AI, we're now talking to machines like they are actual people. We expect logical, human responses from them. Their makers are attaching real, human voices to them (not without controversy). We are being told that they will be our nurses, therapists, and support representatives. Technologists even want to give us digital twins or synthetic versions of ourselves.

People are trying to make machines into very realistic-seeming and feeling entities. But why? I think the reasons vary: to save money, solve human capacity constraints, to persuade us, because it's cool.

Yet, machines are not people. And somehow, that's a point we can't emphasize enough these days.

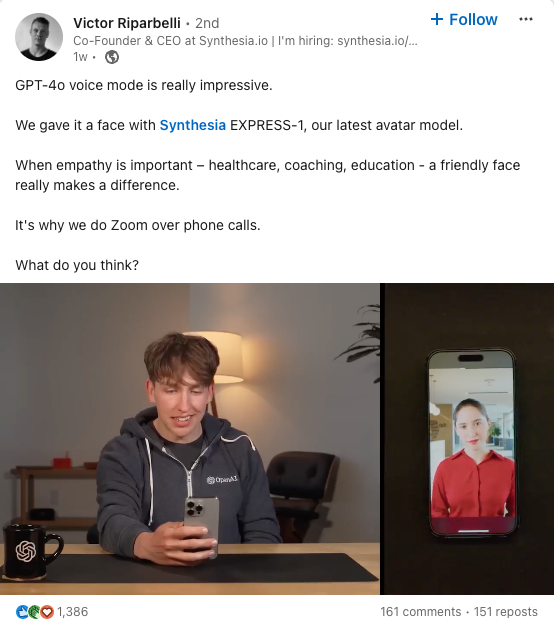

Here’s a recent post from LinkedIn. Others like this pop up on my feed almost daily now.

I'd argue that when empathy is important, you need a real human, not a synthetic one. You need something real behind the friendly face. Empathy is the "ability to sense other people's emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling." Machines are not capable of this.

There are many good uses for generative AI, but I don't think taking empathetic work from humans is one of them. I worry that we're increasingly giving our most creative, human-centric work to machines and forgetting the real value of human interaction – even if it's a little more expensive or inconvenient.

Practical Issues

Beyond the unsettling feeling of talking to simulated people, there are some practical issues with this broad AI initiative (including but not limited to):

- We do not have a clear sense of who owns machine intelligence. Because this is a market-driven initiative, various companies have incentives to make money off these technologies. The pursuit of profits and public benefit are not always compatible – despite what effective altruists say.

- The lack of transparency extends beyond ownership. We do not know what data informs these models or who all the contributors were in the large language model (LLM). We do not have standards around watermarks or encoding the outputs to signal they are artificial. We have nutrition labels for our food but not our media. When anything can be faked and artificially produced, it sows distrust and cynicism across the media and information ecosystem.

- We do not understand how these machines and algorithms work. Even the experts designing the systems will admit that the complexity goes beyond our understanding. Once a prompt goes into the algorithm, it moves so quickly that we cannot be sure of all the factors that contribute to the output. While there are efforts to create explainable AI (xAI), these typically only work with less complex algorithms, which are less accurate or of lower quality. The more accurate, higher-quality algorithms are not compatible with xAI because of their complexity.

- The data that these algorithms are trained on comes from real people who are likely unaware of how their information is being used. Much has been said and written on this topic from a copyright perspective. There is a long list of individuals and companies, including The New York Times and Sarah Silverman, who have come after these technology companies for not requesting, citing, or compensating them for using their data. Generative AI companies are working with platforms and media companies on licensing deals to address this issue, but it is not enough. What's not been thoroughly addressed are the contributions by individual people, unassociated with media companies. They should also be entitled to some compensation for their information and data. Several organizations are committed to this, such as the Data Dividends Initiative and the Data Dividend Project.

- These technologies, like all others before them, will continue to distance us from a richer understanding of the world in pursuit of speed and efficiency. They take the hard labor of a task and reduce it to a simple text prompt. They replace real, human cognitive functions – for good and bad. What will it mean for future generations to not know how to solve problems, even simple ones, without the assistance of AI? Will writing a blog post or creating a presentation without the help of AI be like knowing how to start a fire with flint and a pocket knife?

Reframing AI & the Path Forward

Rather than anthropomorphizing these technologies, we should simply use them as tools. We should grade them on their usefulness instead of their "intelligence." What should matter is the accuracy of the information, not the AI's ability to emotionally connect with humans.

Instead of having pseudo-conversations with these LLMs across the corpus of internet content, we can narrow the context window to more specific needs, like exploring hundreds or thousands of legal documents for details or nuance. There are numerous use cases for document or database exploration. Rather than an agent that looks like a human telling you a gripping story about the findings from their exploration of thousands of pages of legal documents, the information can simply be presented in text or audio.

Many clinical applications already do this. An AI embedded in software shows X-ray images to a doctor and presents recommendations or insights that the clinician may have missed. The clinician has the right and ability to ignore this information and trust their diagnosis or use the information to interrogate their assumptions. This information isn't presented as a virtual, synthetic doctor (for now). It's simple text. The text has likely gone through rigorous usability and bias testing. The practicing, human physician doesn't need the AI-based information to be delivered via a convincing human-like avatar. That inserts a socio-emotional layer into the communicative event that is unnecessary.

Generative AI is a tool, not an actor. I hear people talk about what generative AI is doing to their industry. That's not right. People are using generative AI to transform industries. The technology is not out to get you. Not to invoke 2nd Amendment debate logic, but I do not believe that the only thing that will stop a bad guy with generative AI is a good guy with generative AI. More market competition isn't going to solve these problems.

These tools should be regulated. Their proliferation is inevitable. We are not going to get the glitter back into the jar. But a lack of laws and rules that govern the tools and their makers is not a foregone conclusion.

From content moderation, data and IP protection, liability, discrimination, and transparency, we need to consider minimum standards for the use of these technologies in society. These new rules of engagement should be applied to the companies making the technologies, not just the individual LLMs. All of this will require new regulatory bodies and frameworks, given the step-change difference between this technology and the preceding ones.

There's much to be said (and has already been said) on all the ideas I've written so far. I have a feeling we'll be talking about them for a long time. It's not insignificant that so many people feel uneasy about the technological trajectory we're on. This blog, Mediated, is all about how technology is mediating, or filtering, society and our relationships with each other. Generative AI has only increased the amount of mediation in our lives and we're just at the beginning of feeling the effects.

Member discussion